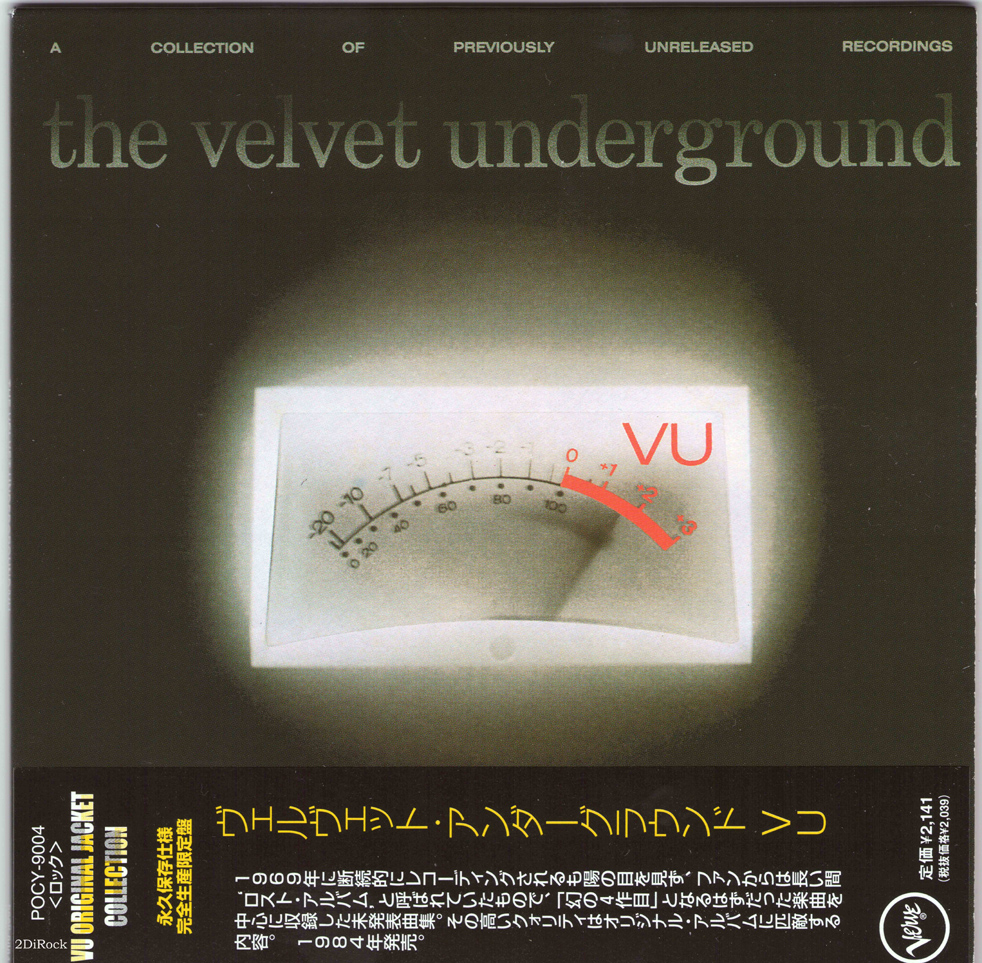

The Velvet Underground (1969) revealed a quieter, often acoustic side to the group. This wasn’t the way to build commercial momentum, so a new musical strategy was pursued. White Light/White Heat (1968) was an uncompromising album, a hard-edged statement that was meant to provoke and shock. It was fine in the beginning, but that niche was confining, and the Velvets wanted to sell records and make a living. For fellow hipsters, the Velvets’ music was as subversive to mainstream ideals of beauty as a Warhol soup can. Only the New York art scene could embrace them. From John Cage and La Monte Young, they learned to be confrontational, but they did it in a rock n’ roll context. They didn’t belong to any musical scene, and they avoided the then-prevalent blues jams, psychedelic sound effects, and rootsy Americana. These tracks remind us that the Velvets were a self-contained unit. Moe Tucker lays down a driving groove, and the guitars circle around it like lightning spires, swinging and building. Reed sounds confident here, and the Velvets work in complicity to serve the song. The version on VU bristles with excitement. It’s a good song, but Reed sounds self-absorbed and it lacks group dynamics. Take for instance the version of I Can’t Stand It on Lou Reed (1972). What makes VU special is the musicianship. Six of VU’s songs are familiar to Reed fans, which appear on four of his studio albums. The prime of this material is contained on VU, which ranks alongside their official releases. These tracks now appear on the VU and Another View compilations. MGM dropped the Velvets and kept their unreleased material, all lost in the shuffle, for fifteen years. The band moved from Verve to MGM, its parent company, but it had no effect on record sales, which remained dismal. John Cale, tired of bickering with Lou Reed, left the band and was replaced by Doug Yule. These tracks had been recorded between 19, a transitional period for the group. Nineteen tracks were discovered in April 1984 while Verve/MGM was preparing a re-release of the group’s first three albums. When VU came out in late 1984, it presented a new chapter to the story we thought we knew, demanding a shift in our thinking. Each note was final, captured in time like a fly in amber. The Velvets’ story had ended with Loaded (1970) and that was that, notwithstanding Doug Yule’s efforts to carry a death corpse. Their studio albums magnified that odd glamour, and what was left unsung was a trigger for our imagination. What we knew about the Velvets was the stuff of legend: Andy Warhol’s Factory, the Max’s Kansas City gigs, the drugs, the strange sexual scenes. In our eyes, they were the real revolution not the hippie commonplace nirvana, but a revolution that was won one convert at a time. It took a new generation of malcontents to discover them, who were hip to the poetry and the musical innovation on those albums. The Velvets were way ahead of their time, punk avatars before the world came around. Those records lay outside the sixties pop spectrum, confounding the love generation with their tonal explorations, unsavory characters, and sheer noise. The seventies saw The Velvet Underground grow in stature as hipster stalwarts, no small feat for a group who sold just a trickle of records in their creative prime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)